About Anthrax

Anthrax

Anthrax is a disease caused by Bacillus anthracis.1,2 While it is primarily a disease of animals, cases of anthrax in humans occur through contact with infected animals or animal products or through intentional spread of B. anthracis spores as a biowarfare or bioterrorism agent.

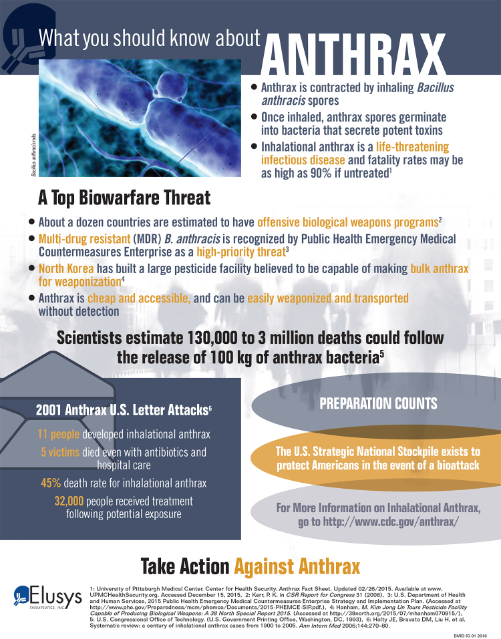

The Threat of Anthrax

- The causative agent, B. anthracis, is widely available. The spores are hardy and tolerant to temperature, humidity, and light.

- Techniques for mass production and aerosol dissemination of anthrax have been developed.

- Multi-drug resistant (MDR) B. anthracis is recognized by Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise as a high-priority threat5.

- B. anthracis has been used in the past as a biological weapon.

Transmission and Spread of Anthrax

B. anthracis spores introduced through the lungs lead to inhalational anthrax.9

Symptoms of Inhalational Anthrax

The median incubation period is 10 days (range 2 – 43 days).2,13 The disease develops in two phases; initially, patients experience a period of flu-like symptoms with a median duration of 3.9 days (range, 3.5 to 4.4 days).11 Nonspecific symptoms reported in this phase include fever, malaise, sweats, cough, dyspnea, altered mental state, nausea and vomiting, headache, and muscle aches.1 A transition to severe illness follows abruptly, with high fever, dyspnea, diaphoresis, and shock.2

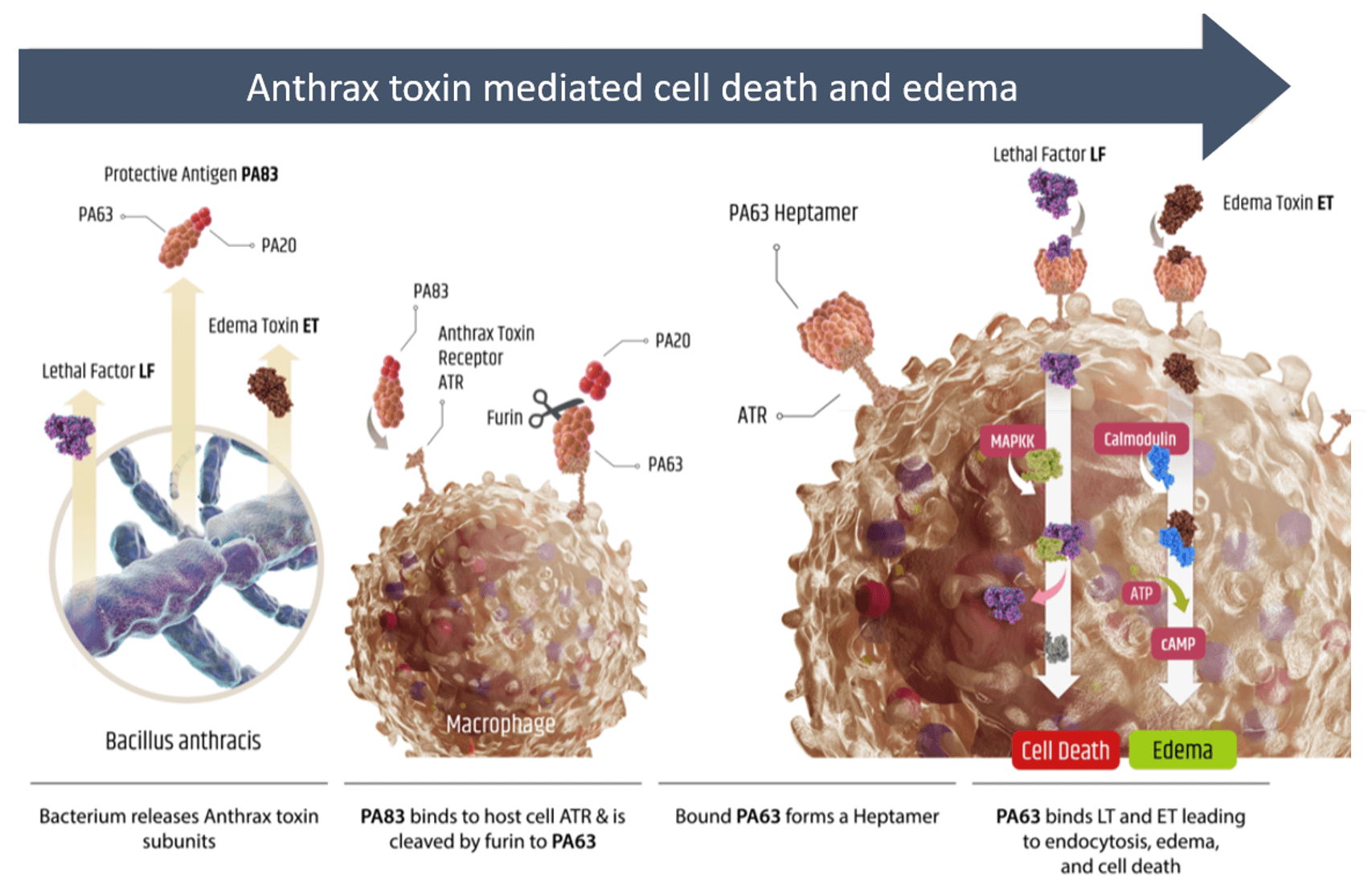

How it Works

- Following infection, B. anthracis can produce anthrax toxin consisting of full protective antigen (PA83), lethal factor (LF), and edema toxin (ET)

- PA83 can bind to anthrax toxin receptor (ATR) on macrophages and be cleaved by cellular furin to release PA20

- Remaining ATR bound PA63 can form a heptamer resulting in the formation of a pore that provides LF and ET with access to the intracellular environment

- LF is a protease that can cleave certain MAP kinase kinases (MAPKK) disrupting cellular signaling and leading to cell death

- ET increases intracellular cAMP levels that can affect membrane permeability and result in edema

Treatment

- Hospitalization is warranted for all patients with suspected inhalational anthrax.9 The CDC guidance for treatment is summarized here.

- Antibiotics target B. anthracis but have no direct effect on toxins that have been released, or the systemic damage they cause. Antitoxins are a class of FDA-approved drugs that complement antibiotics for anthrax treatment by preventing toxins from entering cells and exerting their deleterious effects.

Prevention

- Pre-exposure prophylaxis: Currently, FDA-approved options for the pre-exposure prevention of anthrax include a vaccine and antitoxins (immediate prophylaxis only).

- Post-exposure prophylaxis: For persons who may have been exposed to aerosolized B. anthracis spores but are not showing signs or symptoms of anthrax infection, recommended post-exposure prophylaxis includes antimicrobial therapy or vaccine administration combined with antimicrobial therapy. When alternative therapies are not available, appropriate antitoxins can be used. In this situation, antitoxins would be expected to maintain their treatment effectiveness by preventing toxin formation.

References

- Turnbull, PC. Anthrax in humans and animals, 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2008.

- Inglesby TV, O’Toole T, Henderson DA, et al. Anthrax as a biological weapon, 2002: updated recommendations for management. JAMA 2002;287:2236–52.

- CDC Bioterrorism agents. http://fas.org/biosecurity/resource/documents/CDC_Bioterrorism_Agents.pdf. Accessed January 22, 2016.

- Bower WA, Hendricks K, Pillai S, Guarnizo J, Meaney-Delman D. Clinical Framework and Medical Countermeasure Use During an Anthrax Mass-Casualty Incident. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015 Dec 4;64(4):1-22. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6404a1.

- 2015 Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise Strategy and Implementation Plan. US Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/mcm/phemce/Documents/2015-PHEMCE-SIP.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2016.

- DSNS Fact Sheet. 2014. Accessed December 14, 2015.

- Froude JW, Thullier P, Pelat T. Antibodies against anthrax: mechanisms of action and clinical applications. Toxins. 2011; 3(11):1433-1452.

- IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2012. Prepositioning antibiotics for anthrax. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Hendricks KA, Wright ME, Shadomy SV, Bradley JS, Morrow MG, Pavia AT, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention expert panel meetings on prevention and treatment of anthrax in adults. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet]. 2014 Feb [Accessed December 14, 2015]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2002.130687

- Barr JR, Boyer AE, Quinn CP. Anthrax: modern exposure science combats a deadly, ancient disease. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2010;20(7):573-4. doi: 10.1038/jes.2010.49.

- Holty JE, Bravata DM, Liu H, et al. Systematic review: a century of inhalational anthrax cases from 1900 to 2005. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:270–80.

- Jernigan DB, Raghunathan, PL, Bell, BP, et al. Investigation of bioterrorism-related anthrax, United States, 2001: epidemiologic findings. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:1019-28.

- Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Barry S. Modelling the incubation period of anthrax. Stat Med. 2005;28:531–542